|

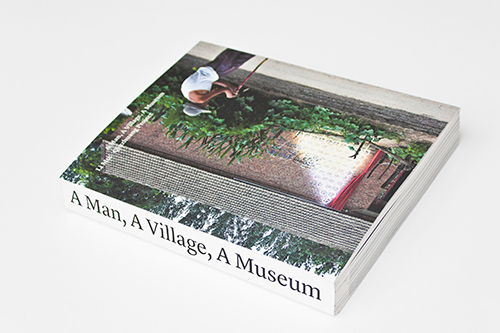

| Foreword for A Man, A Village, A Museum | Date :2017-12-06 | From :iamlimu.org |

| ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ |

![]()

Charles Esche

Time flows. What was air becomes solid. What was energy be- comes matter. The

modern becomes antique, and to follow time means to overturn truths that once

seemed self-evident.

In the early twenty- first century, European and American modern art museums are

faced with questions that are a consequence of that flow of time. They are questions

that the museums them- selves were neither designed for nor willing to answer. What

to do with modern art once it becomes historical? How to handle the material legacy of

modernity—an intellectual, political and cultural movement that began in the European

industrial revolution but has become the imposed inheritance of most of the world?

How should a European modern art museum pre- serve or discard the overabundance

of modern material that has been collected and documented over the past decades?

These are the questions that we at the Van Abbemuseum have been forced by time

(and political developments) to consider and consequently embrace as important as

well as urgent. Of great significance to us is the simple issue of geography. A border

that extends from Los Angeles to Vienna, with a local focus on northwest Europe, limits

our historic collections. An inspired purchase in the early 1970s gave us works by a

single major Russian-Soviet-Jewish artist—El Lissitsky—but beyond that there is little

of great significance. While we can redirect our current collecting activities towards

other cultures and concerns, the map of our modern art is much the same as Alfred

Barr’s first attempt to chart modernism in 1936 on behalf of the new Museum of

Modern Art in New York.

It would be patronising and self-defeating to try to correct the limitations of our

predecessors. Their truths were self-evident not only to them but to all their

colleagues, and it is only with hindsight that their unseen caesuras become visible.

Instead, the challenge for our own (equally blind and biased era) is to think of how this

legacy of Western modernity can be put to good use in the present; can be mobilised

to tell stories that are historical because they show the genealogy of the present and

therefore how we might imagine the future unfolding. This involves, necessarily, that

the patterns of display, conservation and documentation of the modern period be

evaluated anew and replaced by new ways of handling these objects as appropriate to

the time now.

From the Van Abbemuseum’s point of view, our thinking about our collection in this

way is the context that Li Mu encountered when he first suggested his village project

to me at a dinner after the opening of “Double Infinity” in Shanghai. As he says in this

book, I did think his suggestion was crazy, especially as the museum was in the midst

of a two-year process to send a Picasso painting to Palestine, but I also understood it

as absolutely appropriate to what a European museum should do. If the Van

Abbemuseum’s collection could mean anything to anyone in the twenty-first century,

then learning from the actions and reactions of central Chinese villagers seemed as

good a place as any to test this. Li Mu’s proposal required a lot from the museum in

different ways. We needed to be hospitable to the idea in the first place; we needed to

be willing to find financial support at a time of economic austerity and retrenchment;

for the purpose of copying, we needed to measure, analyse and rephotograph artworks

at a level of detail that had never been contemplated in the past. All these demands

undermine the museum’s habitual operations and allow us to learn more about why we

do what we do and what it represents in the world at large. In very concrete ways,

these demands help to answer the question of what a modern collection might mean

today.

The Qiuzhuang Project has taken longer than any of us thought at that time; it has

witnessed changes in China and Chinese cultural policy, as well as cuts and criticism

from Dutch political society about the meaning of art and culture in the Netherlands.

Through it all, Li Mu has persisted. This book represents a full account of his

Qiuzhuang Project and its constant ups and downs—the cold winters, the joys and

fears of a small community, the silences and arguments inside the village and the

moments of intense communication with outsiders. In sum, it is exemplary of how

modern art, can still perform in the world today. Once it is taken out of its gilded

museum cage, it can produce new kinds of social relations in different environments

and forge new links between aesthetics and ethics.

The approach and attitudes in this book and the exhibition that accompanies it need to

be pursued by museums. They should provoke new collaborations in different areas of

the world and with different constituencies of people. Already projects in Congo,

Kurdistan and Palestine are on the horizon of the Van Abbemuseum. Local projects in

Eindhoven between disenfranchised Dutch citizens and artists such as Wochenklausur

and Tania Bruguera are also in progress. These projects all learn from what happened

in Qiuzhuang and this is how the archive of modern art will come to life again outside

the important but limited form of the controlled museum exhibition display. In all these

senses, Li Mu’s Qiuzhuang Project shows us the way forward.

Charles Esche (born 1963, England) is a Museum Director and Arts Curator. He lives

between Edinburgh and Eindhoven.

Since 2004, he has been Director of the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, Netherlands. In

2012, he established together with 6 other European museums the L'Internationale

confederation that aims to establish a European modern and contemporary art

institution by 2017. He curated the 31st São Paulo Bienal in 2014 with Benjamin

Seroussi, Galit Eilat, Luiza Proença, Nuria Enguita Mayo, Oren Sagiv and Pablo

Lafuente. In 2015, he co-curated the Jakarta Biennale in Indonesia.

He is Professor of Curating and Contemporary Art at the University of the Arts London

and is co-editorial dierctor of Afterall Journal and Afterall Books with Mark Lewis.

Afterall is a contemporary art publisher which was launched in 1998 and is based at

Central Saint Martins College of Art and Design. London. It publishes a respected

journal and the Exhibition Histories and One Work of Art series. Afterall also produces

occasional readers such as Art and Social Change edited by Esche with Will Bradley.

|

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

© iamlimu.org 2011 |

|